The Evolution of Digital Vision: A Journey Through the History of Computer Images

Open any app on your phone, and you're interacting with the culmination of nearly 80 years of innovation. The images on your screen — sharp, colorful, instantly loaded — represent countless breakthroughs in how humanity captures, stores, and displays visual information. Each pixel carries the legacy of scientists, engineers, and artists who imagined possibilities that their contemporaries often couldn't comprehend.

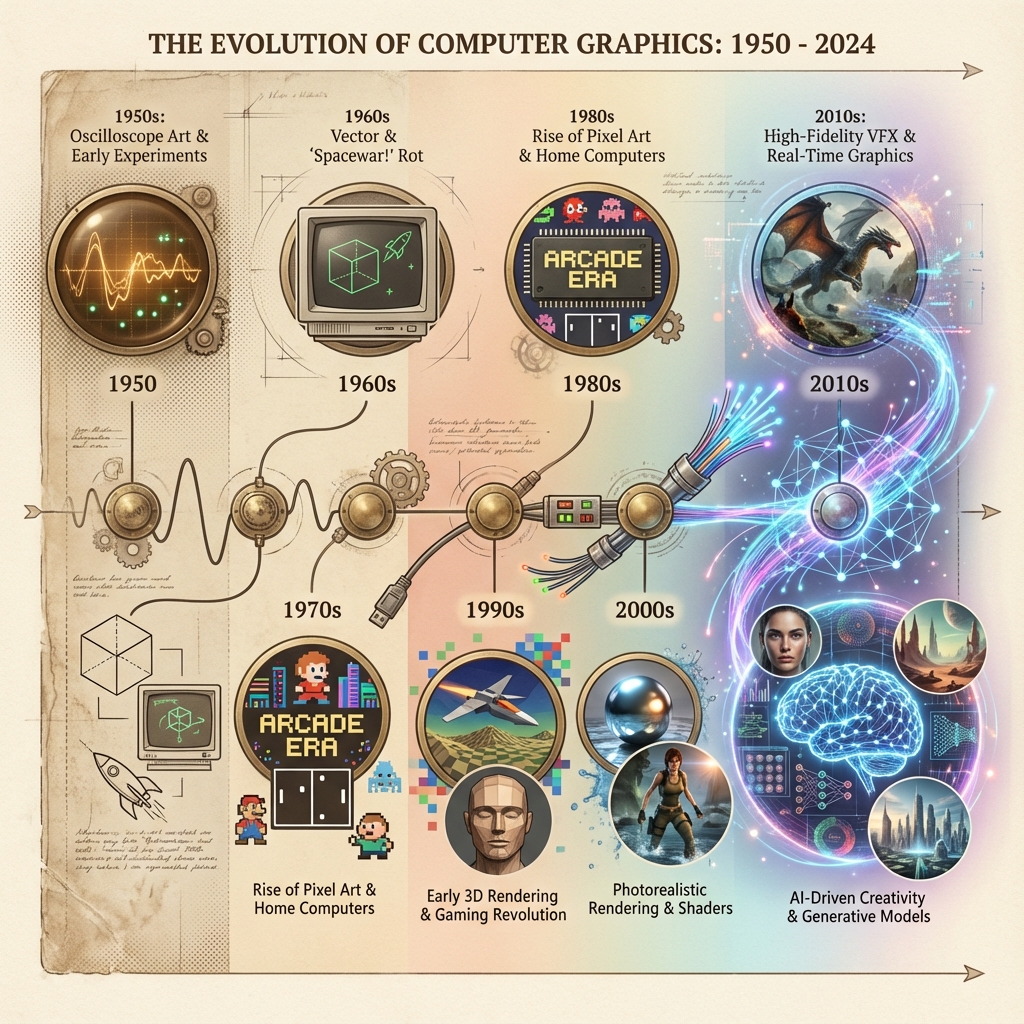

This is the story of how we taught machines to see and show, a journey from flickering oscilloscope dots to AI-generated photorealism. It's a tale not just of technology, but of human ambition to translate the visual world into digital form.

> The Dawn of Digital Vision: 1940s-1960s

The year was 1947. In a laboratory at the University of Manchester, Freddie Williams and Tom Kilburn stared at a cathode ray tube connected to the world's first stored-program computer. What they saw — patterns of dots representing memory contents — were not images in any meaningful sense. Yet they represented something revolutionary: visual output from a computing machine.

Two years later, MIT's Whirlwind computer took the next leap. Designed by Jay Forrester, Whirlwind became the first computer with real-time interactive CRT display. Operators could watch the machine think, seeing calculations unfold as glowing phosphor traces. This wasn't art or photography — it was pure data visualization — but it planted the seed for everything that would follow.

The artistic possibilities emerged almost accidentally. In 1950, Ben Laposky connected an oscilloscope to analog circuits and began manipulating electronic signals to create abstract patterns he called "Oscillons." Exhibited at galleries around the world, these swirling forms became humanity's first computer-generated art. Laposky couldn't store his creations digitally; he photographed them from the CRT surface, a charming reminder of how primitive the technology remained.

The true breakthrough came in 1963 when a PhD student named Ivan Sutherland created Sketchpad at MIT. Using a light pen, Sutherland could draw directly on a computer screen — circles, lines, constraints, hierarchies. The concepts he introduced remain fundamental to every graphics program today. Sutherland's vision was so far ahead that it earned him the Turing Award and established the foundation for CAD systems, animation software, and the graphical interfaces we can no longer imagine computing without.

> The Pixel Revolution: 1970s

The 1970s confronted a fundamental question: how should computers represent images? The answer emerged from work that Russell Kirsch had pioneered in 1957, when he scanned a photograph of his infant son at a resolution of 176×176 pixels — the first digital image from a physical photograph.

By the 1970s, this pixel-based (raster) approach became the standard. Each image became a grid of colored dots, their arrangement determining what we see. The concept seems obvious now, but it required enormous conceptual shifts in how engineers thought about storing and displaying visual information.

Graphics terminals matured rapidly. Tektronix's 4010 series introduced storage tubes that could retain images without constant refreshing, making them practical for engineering and scientific work. The PLATO educational system at the University of Illinois featured plasma displays — bright orange graphics against black backgrounds that students used for everything from chemistry simulations to the first graphical social games.

The decade also spawned computer animation as an art form. In 1972, Ed Catmull and Fred Parke created "A Computer Animated Hand" at the University of Utah, demonstrating that three-dimensional graphics could move with fluid naturalism. Catmull would later co-found Pixar, but the seeds of that revolution were planted in a Utah laboratory, frame by painstaking frame.

Personal computers brought graphics to the masses. The Apple II (1977) displayed 280×192 resolution in six colors — astonishing capability for a machine ordinary people could buy. The Commodore PET and TRS-80 followed, each expanding what home users could visualize on screen.

> Standardization and Explosion: 1980s

The 1980s brought order to chaos. IBM's Video Graphics Array (VGA) standard, introduced in 1987, established 640×480 resolution at 16 colors as the baseline for PC graphics. This standardization meant software developers could create visual programs confident they'd work across machines. The graphics industry finally had common ground.

Image formats emerged to solve the problem of storage and interchange. ZSoft's PCX format (1985) became one of the first widely-used bitmap standards for PCs. Microsoft's BMP format arrived with Windows 1.0 (1986), prioritizing simplicity over efficiency — files were typically uncompressed but universally readable.

Then came GIF. CompuServe introduced the Graphics Interchange Format in 1987, and it quickly became essential to the nascent online world. GIF's clever compression (using the LZW algorithm) kept files manageable over slow modems. Its support for animation and simple transparency made it perfect for web graphics. Even the 256-color limitation felt like abundance in an era when many displays showed far fewer.

Graphical user interfaces matured with Apple's Macintosh (1984) and Microsoft Windows (1985). Suddenly computers needed to draw windows, icons, buttons, and menus constantly. This demand drove innovation in graphics hardware and established visual interaction as the expected norm rather than a luxury.

Three-dimensional graphics moved from research labs to commercial products. Silicon Graphics introduced workstations capable of real-time 3D rendering for professional applications. By decade's end, consumer-level 3D acceleration was emerging, hinting at the gaming revolution to come.

> The Web Era: 1990s

The 1990s began with a compression breakthrough that would shape digital photography forever. The JPEG standard, formalized in 1992, used the discrete cosine transform to compress photographic images to fractions of their original size while maintaining acceptable quality. A vacation photo that might have measured megabytes as raw pixels could become tens of kilobytes as JPEG, making digital photography practical for storage, transmission, and eventually the web.

JPEG's genius lay in understanding human perception. The algorithm prioritizes information our eyes notice while discarding details we'd never miss. Adjustable compression let users choose their own tradeoff between quality and size. For photographs and continuous-tone images, nothing would match JPEG's efficiency for decades.

But JPEG couldn't handle everything. Graphics with sharp edges, text, or limited colors developed visible artifacts at JPEG's lossy compression. The GIF format served these needs but faced a crisis when Unisys began enforcing patents on LZW compression.

The response came in 1996 with PNG — the Portable Network Graphics format. Created explicitly as a patent-free alternative, PNG offered lossless compression that often outperformed GIF while adding crucial features: alpha channel transparency (smooth edges, not just on-or-off), better color depth, and improved compression algorithms. PNG became the format of choice for graphics, icons, and anything requiring precision.

The World Wide Web exploded image consumption. Suddenly millions of people were viewing and sharing digital images daily. Optimization became crucial — every kilobyte mattered when users connected via dial-up modems. Animated GIFs became a cultural phenomenon, from dancing babies to "under construction" signs that now define 1990s web nostalgia.

Adobe Photoshop, released in 1990, democratized professional image editing. Concepts like layers, filters, and masks that had required specialized equipment became accessible to anyone with a computer. A generation of creators learned that digital images were infinitely malleable, establishing expectations that persist today.

> Digital Photography Comes of Age: 2000s

The 2000s witnessed digital cameras transition from expensive professional tools to everyday consumer devices. By mid-decade, camera phones were ubiquitous and film photography had begun its steep decline. This explosion of digital image creation demanded new approaches to quality and organization.

Professional photographers embraced RAW formats — files containing unprocessed sensor data that preserved maximum editing flexibility. Unlike JPEG, which bakes in processing decisions, RAW files let photographers adjust exposure, white balance, and color after the fact. Each manufacturer developed proprietary RAW formats: Canon's CR2, Nikon's NEF, Sony's ARW. Adobe's DNG attempted standardization but never achieved universal adoption.

Metadata standards matured to handle the flood of digital images. EXIF embedded camera settings, timestamps, and GPS coordinates directly in image files. IPTC provided standards for captions, keywords, and copyright — essential for news organizations and stock photography. Adobe's XMP offered extensible XML-based metadata for sophisticated organization.

High Dynamic Range (HDR) imaging emerged as photographers sought to capture scenes that exceeded any camera's native capability. By combining multiple exposures of the same scene, HDR techniques could preserve detail in both shadows and highlights. What began as a specialized technique eventually became a standard smartphone feature.

> The Modern Era: 2010s-Present

Google introduced WebP in 2010, challenging the decades-long dominance of JPEG and PNG. WebP offered both lossy and lossless compression, typically achieving 25-35% better efficiency than JPEG at equivalent quality while supporting transparency and animation. The format faced slow adoption initially — browser support took years to mature — but eventually became a web standard. Today, WebP is often the default choice for optimized web images.

Apple's adoption of HEIF (High Efficiency Image Format) for iOS devices in 2017 signaled another shift. HEIF could compress images to half the size of JPEG while maintaining quality, a remarkable improvement. The format also supported features impossible in legacy formats: multiple images per file, depth maps, and image sequences.

AVIF arrived in 2019 as the current frontier of compression efficiency. Based on the AV1 video codec, AVIF outperforms even WebP, particularly for photographs and high-resolution content. Browser support continues expanding, establishing AVIF as the likely successor to JPEG for photographic content.

Vector graphics experienced a renaissance with SVG's maturation. As responsive design became standard, resolution-independent vector graphics grew essential for icons, logos, and UI elements that must render perfectly at any size. SVG's XML-based structure enabled styling with CSS and manipulation with JavaScript, integrating vector graphics deeply into web development workflows.

Real-time rendering capabilities transformed both games and professional visualization. WebGL brought hardware-accelerated 3D to browsers. Consumer graphics cards achieved performance that would have seemed impossible a decade earlier. Real-time ray tracing — once strictly the domain of offline rendering — became available in consumer hardware, blurring the line between game graphics and film production.

> The Frontier: AI and Beyond

The current revolution centers on artificial intelligence. Models like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion can generate photorealistic images from text descriptions, capabilities that seemed like science fiction just years ago. These systems don't capture physical reality — they synthesize entirely new images based on patterns learned from millions of examples.

This raises questions we're only beginning to explore. When anyone can generate convincing images of anything, what happens to photography as evidence? How do we authenticate genuine images? The technical and social implications will unfold for decades.

Neural compression techniques promise another leap in efficiency. Rather than applying mathematical transforms like DCT, neural networks can learn optimal representations for different image types. Early results suggest dramatic compression improvements, though computational requirements remain challenging.

Computational photography has transformed smartphone cameras into systems that would astonish engineers from any previous era. Portrait mode synthesizes depth-of-field effects that once required expensive lenses. Night mode stacks dozens of exposures to capture scenes too dark for any single frame. HDR processing happens automatically, invisibly. The camera app on a modern phone contains more computational photography sophistication than entire research departments possessed a generation ago.

Augmented and virtual reality demand entirely new imaging paradigms. Light field cameras capture directional light information enabling post-capture focus adjustment. Volumetric video captures three-dimensional scenes for true 360-degree viewing. Holographic displays remain largely research projects but edge toward commercial viability.

> The Continuing Journey

From flickering oscilloscope traces to AI-generated photorealism, the trajectory of computer imaging reflects an accelerating cycle of innovation. Each era builds on foundations laid by previous breakthroughs, capabilities unimaginable to earlier pioneers becoming commonplace within years.

The fundamental challenge remains unchanged: translating visual reality into digital form that can be stored, transmitted, and displayed. Yet the solutions grow ever more sophisticated. We've moved from dots on CRTs to billions of precisely-controlled pixels. From kilobyte-scale images to gigapixel captures. From hand-drawn vector curves to AI-synthesized scenes indistinguishable from photographs.

What remains constant is human ambition — the drive to capture, create, and share visual experiences that machines can preserve and reproduce. The history of computer images is ultimately a story about extending human vision beyond the limitations of biological perception and physical proximity.

The most exciting chapters may still be unwritten. As computational power continues its exponential growth and new techniques emerge from research labs, the possibilities for digital imaging seem bounded only by imagination. For nearly 80 years, that boundary has consistently expanded beyond what any generation expected. There's little reason to think the next 80 years will be different.

This exploration of computer imaging history traces how technological innovations transformed our digital visual landscape. For practical guidance on choosing formats today, see our Complete Guide to Image Formats. To understand the role of vector graphics in modern web development, explore our Complete Guide to SVG.